6 years ago · Archcare

Understanding: OCD

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, or OCD, is one of those mental illnesses that everyone has heard of. This is partly because society tends to use the term as shorthand for someone who is quite clean, or who likes things to be organised, or who is very particular about how they fold their t-shirts. The phrase ‘I’m a bit OCD’ has become so commonly used that most people probably think that they have a good idea of what it’s like to suffer from OCD, but the reality is very, very different, and often much more difficult to live with, than just enjoying a neat and tidy kitchen. In fact, individuals with OCD and organisations that represent them have asked that the term not be used so casually to describe general preferences that most people experience.

In this blog we’re going to talk about what OCD actually is, how it manifests in different people, and what treatment options are available.

What is OCD?

Well, as the name suggests, OCD is made up of two different kinds of symptoms; Obsessions and Compulsions.

Obsessions are defined as intrusive or unwelcome thoughts, feelings, anxieties or images that appear in the mind seemingly without cause. Lots of people will experience this kind of thing, if you’ve ever felt anxious or nervous then you almost certainly know what it feels like to get stuck on a particular thought that you can’t seem to shift, or to have negative feelings appear in your mind suddenly. Sometimes these obsessions are called Intrusive Thoughts. The vast majority of people have experienced intrusive thoughts to some degree, if you’ve ever been in your car and have had a sudden urge to steer into oncoming traffic then you’ve had an intrusive thought, and usually they’re totally manageable and easy to ignore. What sets OCD aside from this kind of every day experience is their intensity, but also that they appear alongside Compulsions. Compulsions are defined as repetitive or ritualistic actions that are taken in an attempt to reduce or manage the anxiety associated with these obsessions.

Obsessive cleaning is one of the more common symptoms of OCD.

You’re probably aware of concept of compulsions. Whenever OCD is portrayed in the media, compulsions are generally expressed in one of two ways; hand-washing or flicking light switches. It’s true that these are common compulsions for people with OCD, but they are far from the only compulsions. Generally, compulsions fall into one of the following categories:

- Washers are afraid of contamination, and will wash or clean themselves or their surroundings compulsively.

- Checkers repeatedly check and confirm things, such as locks or ovens, to confirm that they are safe.

- Doubters and sinners are afraid that if everything isn’t perfect and completed in specific ways then bad things will happen.

- Counters and arrangers will attempt to organise and arrange things in their lives and often display obsessive behaviour or superstitions relating to coordination, counting, numbers and structure.

- Hoarders fear that something bad will happen if they throw anything away, and will often collect large quantities of items or belongings.

As you can see, some of these types of compulsion have a kind of logic behind them. We can understand the anxiety associated with feeling dirty or messy, and we can see why someone would check locks and appliances. Others, such as counting or obsessively organising objects, are more superstitious in nature, and may be trickier to comprehend if you don’t suffer from OCD yourself. It’s important to understand that compulsions are real to sufferers of OCD, and that just because they don’t make sense to us doesn’t mean that they can be dismissed or ignored.

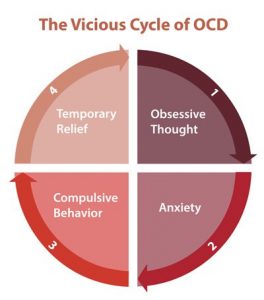

Completing compulsive behaviour usually doesn’t lead to any pleasure, but may reduce anxiety temporarily, providing some brief relief from the obsessive thoughts. This can lead to a vicious cycle, whereby obsessive thoughts lead to anxiety which leads to compulsive behaviour, which then results in temporary relief followed by further obsessive thoughts.

What is the impact of OCD?

Usually there wouldn’t be a need to include this section. Most people can inherently understand the harm caused by anxiety or depressive thoughts or hallucinations, those things are obvious. But it can be harder to truly understand the experience of someone with OCD and all the myriad of ways that it can impact on their life. Take a second to consider how long it would take to check and double check the light switches, doors and windows in each room in your house before you could leave, and what changes you would need to make to your life in order to accommodate this behaviour. It can be easy to see how the condition can end up dominating every aspect of your life, and how the obsessions can end up spiralling out of control.

Checking locks is a way of controlling the physical environment.

And control is a very important aspect of OCD. Scroll back up and look again at the categories of compulsions from earlier on. What do they all have in common? They all relate to attempts to impose control over things in our lives that are chaotic, unmanageable, unknowable or outside our sphere of influence. They all relate to a sense that if we do not complete these very specific actions, or take measures to reduce risk, that bad things will happen to us or people that we love. We all understand this to some degree, we’ve all sat at home at night on our own and heard a noise and been freaked out, and maybe we’ve then gone and checked all the doors and windows even though we know that they’re all closed and locked. We’ve all got halfway to the car before suddenly wondering whether we remembered to turn the oven off, even though we’re sure that we did, and had to go back to double check so that we can relax. Our brains are wired in such a way that we tend to assume the worst so that we can plan effectively, and we instinctively attempt to impose order and control over things in our lives. Well, people with OCD experience these very same feelings, they just experience them more often and at a much greater intensity, often to the point that they may struggle to function, and may become overwhelmed with their compulsions.

If you have time, this is a really interesting documentary about individuals living with OCD:

How is OCD treated?

If you’ve read any of my other blogs about specific mental illnesses, this will be a familiar section to you, because OCD is treated in a very similar manner to other mental health conditions; with a combination of medication and psychological therapy.

The primarily kind of medication used to treat OCD is the same kind of medication used to treat most kinds of depression and anxiety; Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors, or SSRIs. This kind of medication treats OCD by reducing general levels of anxiety, and therefore reducing the obsessive thoughts that drive the compulsive behaviour. For relatively mild cases of OCD, this may be all that is needed, but in more serious cases a course of psychological therapy may be required. This therapy is usually Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, and is particularly effective at treating OCD as it teaches sufferers practical techniques that can be used to manage the intrusive, obsessional thoughts. This will generally include mental exercises, tactics for reducing anxiety and verbal prompts and reminders that help to move the mind away from the cyclical thinking that can lead to compulsive behaviour. These methods are built around the concept that the mind is a muscle that needs to be exercised and trained, and that with discipline and repetition we can build new connections so that anxiety doesn’t automatically lead to compulsive behaviour. This can include carefully encouraging sufferers to engage with their anxieties and take action that makes them feel uncomfortable, or acknowledge anxiety caused by inaction, in a controlled setting without seeking relief via compulsive behaviour. It isn’t a quick process, and can be very stressful and difficult for people seeking treatment, but success rates are good.

It’s very important to remember that simply refusing to indulge OCD symptoms, or dismissing them as silly or pointless, will not work, and can even make things worse. Some people believe that if someone with OCD would just stop washing their hands or checking the windows that this would prove that everything is fine and would ‘cure’ the compulsive behaviour. OCD treatment is not that simple, and any attempts to encourage individuals to engage with their anxieties or face their fears should only be made in controlled environments by professionals. This kind of therapy is generally known as Exposure Therapy, and may be used in place or, or in conjunction with, CBT.

Exposure therapy works by encouraging the individual to confront situations or objects that cause anxiety without relying on ritualistic behaviour. Typically this is done in a slow, controlled manner, starting with small amounts of exposure for short periods of time which is tolerated for as long as possible, and moving on to longer and more intense exposure once this is manageable. For example, someone who has rituals related to cleaning may be encouraged to touch or handle dirty objects for short periods of time. In the past this form of therapy was done in a much faster and more sudden manner, typically by introducing the individual to high levels of stress and anxiety quickly in the hope that this may have a similar effect to pulling a plaster off quickly. Nowadays this is not generally advised, as it can cause levels of stress that are difficult to tolerate.

A good way to think about exposure therapy is to think about getting into a cold swimming pool. Getting into the pool slowly, bit by bit, and waiting for your body to acclimatise to the new temperature is a lot less shocking and uncomfortable than jumping in quickly. It takes something that could be very stressful and upsetting and makes it manageable by doing it slowly in a controlled manner, and as we know maintaining control is often very important for people with OCD.

Exposure therapy is complicated and requires professional guidance and should never be attempted without proper training and supervision, as if done incorrectly it can actually make the symptoms worse.

If you or anyone you know is suffering from OCD, or you are worried that you are developing symptoms, you should always contact a GP. OCD rarely gets better on it’s own, so you should always seek help if you are concerned. If you need immediate help, or are worried that you may harm yourself or someone else, you should call 999 immediately.

Read more Comments Off on Understanding: OCD